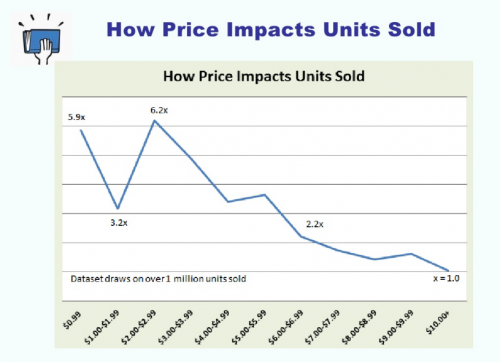

Okay, I’m sure a lot of you have read this NYT article by now (or at least heard it mentioned here on Murderati) which tells us that the minimum output of books per year for a professional author is now two. Per year. Double what people are used to thinking.

In the E Reader Age, a Book a Year is Slacking

And the article links this new phenomenon to the e book revolution.

Well, I would strongly disagree. MOST of the authors I know who make a good living at just writing books have been writing AT LEAST, at the VERY least, two books a year for longer than I’ve been in the author business. There are very few I know who can afford the leisurely pace of a book per year. (I dream of being able to afford that luxury…)

It was one of the first things I noticed when I moved from screenwriting to the author business in 2006. Successful writers write a LOT of books. Tons. Staggering numbers. Plus stories and any number of other things. (I felt like a total slacker until I realized if I had been writing books instead of screenplays for the last 11 years I would have those kinds of numbers, too.)

Of course, there’s a catch that we all have to be wary of. How long does it take to write a GOOD book? When are you starting to risk, well, dreck?

I wanted to think and talk about that today.

From the beginning of my (still quite short, really) author career, one of the questions I have gotten most often at book signings and panels is, “How long does it take you to write a book?”

My feeling is what’s always being asked is not how long it takes me to write a book, but how long it would take the person asking to write a book. Which of course, I have no way of answering, unless it’s to cut to the chase and shout, “Save yourself! Don’t do it!” But that’s never the question, so I don’t say it.

What I started out answering instead was, “About nine months.” Which, from Chapter One to copyedits, used to be true enough. But I’m getting faster. And the paranormals I write take more like two months. And of course with e publishing, the whole process of publishing has changed, and the time frame has changed, too.

I wrote three and a half books last year. One YA thriller, THE SPACE BETWEEN, one non-fiction writing workbook, WRITING LOVE, one paranormal, TWIST OF FATE (coming out in 2013), and half of my latest crime thriller, HUNTRESS MOON, which will be out next month. (And technically I also outlined another paranormal, KEEPER OF THE SHADOWS, which will also be out in 2013. Outlining is writing, too!).

This year I will have written another four or possibly four and a half. Two paranormals, another thriler and a half, and – either a half or whole other SOMETHING yet to be determined.

So that’s a lot of books. How long did it take me to write any one of those? It’s really hard to say when those projects are constantly overlapping.

But the fact is, in almost every case, the real answer to the question of “How long?” is almost always: “Decades.”

Because honestly, where do you even start? I’m quite convinced I’m a professional writer today because my mother made me write a page a day from the time I could actually hold a pencil. At first a page was a sentence, and then a paragraph, and then a real page, but it was writing. Every day. It was an incredibly valuable lesson, which taught me a fundamental truth about writing: it didn’t have to be good, it just had to get written. Now I make myself write however many pages every day. And now, like then, it doesn’t have to be good, it just has to get written. Some days it’s good, some days it’s crap, but if you write every day, there are eventually enough good days to make a book.

Then there were all those years of theater, from writing and performing plays in my best friend’s garage, to school and community theater, to majoring in theater in college, to performing with an ensemble company after college. Acting, dancing, choreography, directing – that was all essential training for writing.

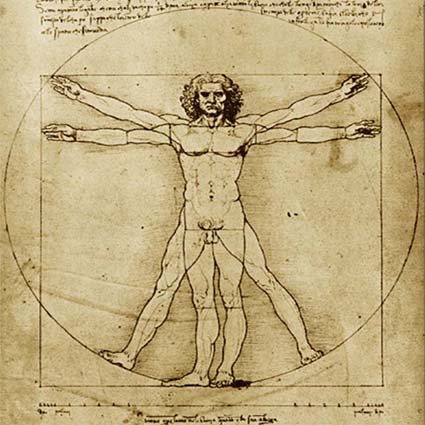

And then the reading. Again, like probably every writer on the planet, from the time I could hold a book. The constant, constant reading. Book after book – and film after film, too, and play after play – until the fundamentals of storytelling were permanently engraved in some template in my head.

Hey, you may be saying, that’s TRAINING. That wasn’t the question. How long does it take to WRITE A BOOK?

I still maintain, it takes decades. I think books emerge in layers. The process is a lot like a grain of sand slipping inside a clamshell that creates an irritation that causes the clam to secrete that substance, nacre, that covers the grain, one layer at a time, until eventually a pearl forms. (Actually it’s far more common that some parasite or organic substance, even tissue of the clam’s own body, is the irritant, which is an even better analogy if you ask me, ideas as parasites…)

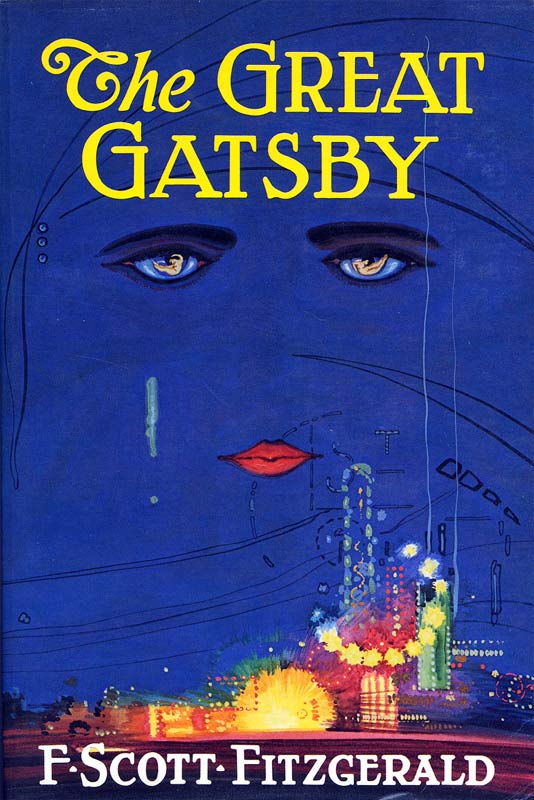

Let’s take a look at Book of Shadows, the thriller I’ve just gotten back from my publisher and put out myself as an e book last week.

When did I start Book of Shadows? Well, technically in the fall of 2008, I guess. But really, the seed was planted long ago, when I was a child growing up in Berkeley. (The Berkeley thing pretty much explains why I write supernatural to begin with, but that’s another post.) Those of you who have visited this town know that Telegraph Avenue, the famous drag ending at the U.C. campus, is a gauntlet of fortune tellers (as well as clothing and craft vendors and political activists and, well, drug dealers.).

Having daily exposure to Tarot readers and psychics and palm readers as one of my very first memories has been influential to my writing in ways I never realized until I started seeing similarities in Book of Shadows and my paranormal The Shifters, and discovered I could trace the visuals and some of those scenes back to those walks on Telegraph Ave.

Without mentioning an actual number, I can tell you, that’s a lot of years for a book to be in the making.

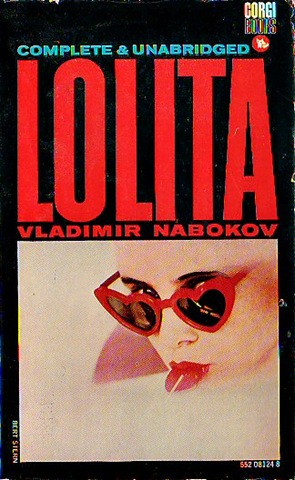

Over the years, that initial grain of sand picked up more and more layers. Book of Shadows is about a Boston homicide detective who reluctantly teams up with a beautiful, enigmatic practicing witch from Salem to solve what looks like a Satanic murder. Well, back in sixth grade, like a lot of sixth graders I got hooked on the Salem witch trials, and that fascination extended to an interest in the real-life modern practice of witchcraft, which if you live in California – Berkeley, San Francisco, L.A. – is thriving, and has nothing at all to do with the devil or black magic. Hanging out at the Renaissance Pleasure Faire (more Tarot readers!), I became acquainted with a lot of practicing witches, and have been privileged to attend ceremonies. So basically I’ve been doing research for this book since before I was in high school.

And my early love of film noir, and the darkest thrillers of Hitchcock, especially Notorious, started a thirst in me for stories with dark romantic plots that pit the extremes of male and female behavior against each other; it’s one of my personal themes. Book of Shadows is not my first story to pit a very psychic, very irrational woman against a very rational, very logic-driven man; I love the dynamics – and explosive sexual chemistry – of that polarity.

So to completely switch analogies on everyone, this book has been on the back burner, picking up ingredients for a long, long time.

Now, what pulls all those ideas and layers and ingredients into a storyline that takes precedence over all the other random storylines cooking on all those hundreds of back burners in my head (because that’s about how many there are, at any given time), is a little more mysterious. Or maybe it’s not. Maybe storylines leap into the forefront of your imagination mostly because your agent or editor or a producer or executive or director comes up with an opportunity for a paycheck or a gentle reminder that you need to be thinking of the next book or script if you ever want a paycheck again. I know that’s a powerful motivator for me. So speed in writing comes partly out of practical necessity.

But the reason a professional writer is able to perform relatively on demand like that is that we have all those stories cooking on all those back burners. All the time. For years and years, or decades and decades. And if a book takes nine months, or six months, or a year to write, that’s only because a whole lot of stuff about it has been cooking for a very, very, very long time.

A long time.

And I’m wondering, lately, if one of the keys to writing faster without killng yourself doing it is to check those pots bubbling back there on the mental back burners more often. Taking the time every few months to just sit quietly and free-form brainstorm on paper or on the screen… and see what ideas might be more done than not. Sometimes random and seemingly separate ideas can suddenly combine to create a full story line. Because I’m quite sure that we ALL have books that have been cooking back there for decades now. Maybe it’s time to take them out.

So writers, how long does it take YOU to write a book? Or your latest? How many stories do you figure you have on the back burner at any one time?

And readers, do you ever notice certain themes – or recurring scenes or visuals – in your favorite authors’ books that make you suspect that story seed was planted long ago?

And here’s one worth discussing: is anything MORE than a book a year cheating the book?

– Alex

————————

All right, Nook people, you keep asking, and for a limited time I’m putting The Unseen, The Harrowing and The Price up at B&N.com for Nook: $2.99 each.