by Jonathan Hayes

There’s been a recent flurry of activity over the Brian De Palma-directed, Oliver Stone-scripted, Al Pacino-larded Scarface. The celebrations, complete with cast reunion and one-off screenings nationwide, are not about an anniversary (the movie came out in 1983), but release fanfare for a new Blu-ray edition. In truth, Scarface has such a huge following that no particular special occasion would be necessary to celebrate it.

The film, released to middling reviews and decent box office, has flourished over the last almost three decades as a burgeoning cult obsession, driven by VHS, then DVD releases. Its popularity was particularly obvious among rappers – every hip hop star showcased on MTV Cribs had that poster of a brooding, Hamlet-esque Tony Montana, on the edge of darkness and light, hanging on his media room wall; indeed, this is probably how the film’s following was sustained, with younger fans picking up on the endlessly repeated meme.

The movie’s appeal is obvious, particularly to disadvantaged young men. The American Dream writ large, Scarface tells the story of Tony Montana, a Cuban thug ejected from Havana during the Mariel boat lift. Landing in Florida, through ambition and ruthlessness, Tony becomes a cocaine kingpin, becoming hugely wealthy and losing everything in the process. It speaks to the disenfranchised directly, celebrating the outsider, implying that even the marginalized can have whatever they want, if they have the drive and the cojones.

Tony’s rewards are the dream of any 14 year old boy – fountains of money, amazing cars, a mansion, cool guns, and Michelle Pfeiffer at her most luminous. As a movie, Scarface is a pop song, an agglomeration of hooks – Tony’s sexy toys, the graphic violence (including an impressive chainsaw dismemberment in a shower in a pre-gentrification Miami Beach), Stone’s quotable dialogue (“Say hello to my li’l friend!” alone is probably uttered hundreds of times every day) and Pacino’s manically bizarre take on the Cuban accent – Stone may have written “cockroaches”, but with “CACK-A-ROACHES!!!!”, Pacino made it his own. Much as he did with “HOO-AHH!!!” in the abysmal Scent of a Woman. (A side note: why did the Academy acknowledge him for that performance? Giving him the Best Actor Oscar was like injecting the Tasmanian Devil with coffee and methedrine and setting it loose in Disney World on Orphan Visiting Day; since then, with every one of his performances, Pacino may not actually say “HOO-AHH!!!”, but you can feel him thinking it…)

As a kid, I spent a lot of time in art house and rep cinemas – the Coolidge Corner, the Harvard Square and the Brattle in the Boston area, the Scala and the Ritzy in London – enduring endless double bills of Kurosawa and Truffaut, the Marx Brothers and Bogart. When I was growing up, the big cult movies were countercultural/alternative, like King of Hearts and Harold and Maude. If Scarface is something of an evergreen, what are the current cults?

Wait: I want to mention one film that is, I think, both a cult film and a classic, in the non-ironic sense. Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner, released the year before Scarface, is sci-fi noir, an existentialist picture from a Philip K. Dick short story about a detective assigned to track down androids who are “more human than human”; in the process, Deckard (Harrison Ford) is forced to question his own humanity. The film’s philosophical themes are buried in a glorious miasma of visionary filmmaking, centered about Syd Mead’s concept – which felt unprecedented at the time – of a future not all slick and shiny and “futuristic” in that smooth, modern Kubrick’s 2001 sense, but of a civilization that had progressed technologically but not ideologically, developing organically in the ruins of its own crumbling cities, consuming the environment, exterminating natural life on earth until it’s forced to flee the planet.

With unparalleled art direction, sound design and special effects, Blade Runner is, for my money, a great film. It’s flawed, though, which is why it remains mostly a cult object – cost and time overruns, endless arguments with the studio, which took control away from Scott to deliver an aggressively edited release with an overdetermined noir voice-over, and the existence of seven different release cuts have all interfered with the film’s establishing itself as a true classic. Blade Runner is more worthy of a Blu-ray edition than Scarface; thankfully, it is the object of a five disc Blu-ray set, containing several different cuts of the film. You’ve probably seen it, but if not, watch it before the arrival of Scott’s new “installment” of the “Blade Runner franchise”, a project announced a couple of weeks ago.

To my eye, the two contemporary films that command the biggest cult following among Millennials (aka Generation Y, aka Generation Next, aka Generation Net) are Fight Club and Léon (released in the US as The Professional). I base that opinion both on the multitude of references to them rattling around on Twitter and Facebook, and because I’ve been surprised by how frequently I encounter them when I’m looking at tumblrs (tumblrs are blogs which make it particularly easy to share photographs and videos and audio, rather than being text-oriented. My own tumblr is a repository for images and sounds I’ve come across that I want to share; they may be beautiful, arresting or disturbing, but they all evoked a reaction in me).

Citations of the two films break down along lines of sex; unsurprisingly, Fight Club shows up mostly on dude tumblrs, whereas it’s (usually) the chicks who post from The Professional. Both films are very strong visually – something I think is key in catching the attention of the post-MTV generation.

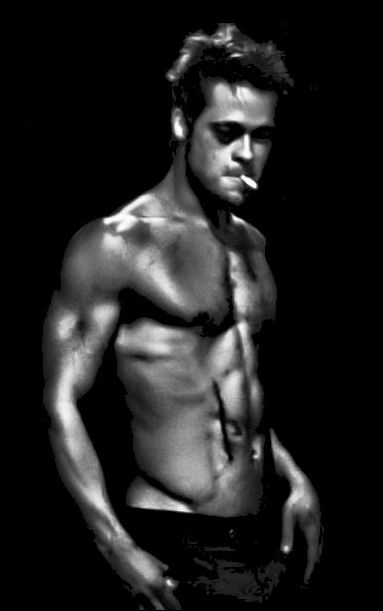

Fight Club is David Fincher’s 1999 adaptation of Chuck Palahniuk’s 1996 novel of the same name. You’ve probably seen it, but if not it’s a lacerating satire about… well, a lot of things. An insomniac traveling salesman who feels emotionally disconnected from the world meets a handsome, id-driven stranger. They become friends, and together start a “fight club”, in which men meet for no-holds-barred bareknuckle fist fighting. The club, lead by the homicidally reckless Tyler Durden, evolves into an anti-corporate movement, pranking companies and attacking consumerism head-on, with each episode of sabotage more destructive than the one before, everything leading up to an explosive twist ending.

At its core, the film grapples with the classic post-modern anguish over the Death of the Real. The members of the fight club are responding to a prevalent sense of alienation from reality, from real feeling. They live in a world where values are dictated by marketing, where advertising is treated as art, and where high end consumption is considered a valid life goal. For young men who’re increasingly realizing that their lives will never be like the lives they’ve been shown on TV (they’ll never live in a loft in New York City with seven attractive strangers, they’ll never drive a Bentley convertible, and, even though they “think she’s a skank”, they’ll never get the chance to fuck Snooki) the anarchist message is an instant hook. If you can’t have something that you’re constantly being shown as visible and imminent, the fantasy of burning it all down is incredibly seductive.

An awareness of the shallowness of the goals of the generations that immediately preceded them – Generation X, the Baby Boomers – is said to mark Millennial thinking. Millennials want careers – want lives – that have meaning and richness. It’s not about money, but about valid experience. This extends into the realm of physical action: I think that one of the reason that extreme sports, sports with a high risk of physical injury, like skateboarding and ultimate fighting, are popular now is because pain is an immediately and undeniably real experience. I think this is part of the reason why the 2000’s were the era of Jackass, the era of the emergence of the Modern Primitive culture of piercing and tattooing.

Fight Club scratches this itch for young men. They watch the film, relate to its seditious messages, accept the homoerotic undertones of the unreliable narrator’s relationship with Tyler Durden. And at the end of the day, the movie looks fantastic, and Tyler Durden looks just so freakin’ cool in those shades and bro shirt and red leather jacket, up there on that glossy 42” Sony LED screen in the living room.

One of the major ways in which experience for the Millennials has been mediatized and mediated is in the experience of love and sex – the latter far more than the former. Any 13 year old boy or girl can show you how to access hardcore online pornography for free, and a huge percentage of teens have sent or received photographs of themselves or their peers naked or having sex. I’m fascinated by the amount of erotic material in their tumblrs, both the stuff that’s on the edge of hardcore, and the frankly pornographic, with visible penetration. This goes for both the male and female bloggers. And while some of the females may be using porn to catch the attention of the boys, I think that many young women like/embrace/are aroused by it.

I’m not interested in questions about the morality of pornography, but I do find its embrace interesting and problematic, particularly in terms of the expectations young people will have in terms of how sex will work inside (and outside) their main relationships.

Blogs – tumblrs perhaps even more so than traditional text blogs – are declarations of both identity and aspiration. The blogger filters the internet, sharing material to show how the blogger wants to be seen, the things they fear, the things they want for themselves. They can be endlessly engrossing, particularly when you come across a blogger who shares your world view. I’m the same way – my tumblr (which I assemble almost at the level of spinal reflex, grabbing and posting images and music that have triggered something in me, knowing that I’m disclosing complex but pretty legible truths about myself) is my way of filtering my experience of the world (as viewed through the fish-eye lens of the internet). I see my tumblr as a visual and acoustic form of DJ’ing, of imposing order on a world out of control.

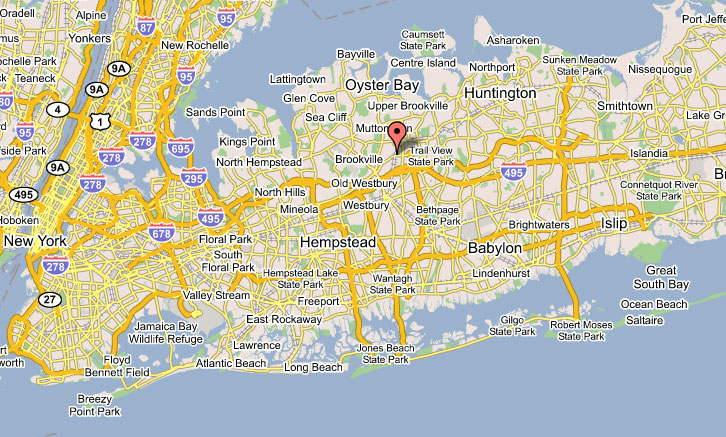

The Professional (aka Léon) is a stylish crime film by the prolific lowbrow pulp French director Luc Besson (The Big Blue, La Femme Nikita), who must never be confused with Robert Bresson, the highbrow French director of such films as 1951’s The Diary of a Country Priest and 1959’s Pickpocket. A little girl (Natalie Portman) witnesses the killing of her entire family by a bunch of corrupt, drug-dealing DEA agents led by Gary Oldman. She is saved by the intervention of a neighbor, a bearish, taciturn hitman (Jean Reno), who hides and protects her. He becomes a father to the orphan, and she in turn brings him out of his shell, freeing him from the rigorous code of living he’s adopted to survive all these years. Of course, her involvement in his life compromises it, with ultimately disastrous results.

I like this film a lot, but largely for visual reasons – Besson’s films tend to poke around notions of crime and redemption without doing much with them, but at the end of the day, he inherited the mantle of beautiful, advertising-inspired filmmaking from Jean-Jacques Beneix (Diva, Betty Blue), and strong visuals work for me

The essential relationship in the film – between Mathilda Lando, the appealing, inquisitive 12 year old and Leon, the grunting, barely socialized hit man – is, I believe, at the root of the appeal for the girls who post stills and clips. It’s an odd, uncomfortable relationship, hovering between the childlike, the revelatory, the protective and the incestuous. Leon (the hitman) is the ultimate father figure – he’s a kind of indestructible machine who will protect the little girl against any attack. He is strong, silent and, in his ultimate self-sacrifice, the epitome of the loving father.

In turn, Mathilda looks after him, this brooding, homicidal manchild, making sure he’s fed and watered, defusing his alienation and isolation, abnegating his nihilism to connect him once more to the world. And, once his feet touch the ground, he is no longer an immortal, but human, vulnerable in every sense of the word.

I suppose that’s part of the character’s romantic appeal: he is one particular ultramasculine male archetype, and she comes along, with her innocence and love, and unlocks his armour to reveal the loving Daddy within. And he loves her, and protects her, at extraordinary cost to himself.

But I also found their relationship a little creepy, the way she becomes his mother, almost his wife in the process. It has that tang of incestuousness, that little echo of the taboo – particularly when you come across photographs of Mathilda and Leon right next to a hardcore animated gif of a couple having violent sex.

I think Mathilda herself – an avatar of innocence, of vulnerability in the face of an ugly, brutal, monstrous world – is another reason the film is so appealing to young women. Millennials, I believe, relate more to the romantic notion of the childlike waif, the orphan, than have previous generations. I don’t know if this is because the world is a more frightening place now than it was before, or if it is because changing patterns of child raising have resulted in timid, cosseted children.

Anyway, I’ve droned on long enough about this. Both films are worth your time. And so are tumblrs! They’re a fascinating lens onto what people are thinking and doing these days. You can start with my tumblr, if you’d like: Millennials are nothing if not democratic, so tumblrs are really hyperlinked – the photographs I post are usually linked to the original poster. This way, you can click on an image that appeals, track it back to the original tumblr, then page through that person’s tumblr looking for more images that you like, and in turn track those back to their original pages, bookmarking the ones you like. Et cetera, et cetera, et cetera.

Oh, a note about navigating tumblrs: they all have different layouts, but if you click on the tumblr’s name at the top of the page (eg, mine is AFTER THE TORCHLIGHT), that will take you back to the current front page of the tumblr. Some tumblr layouts show 15 posts at a time, others let you scroll infinitely. To quickly view all of the posts in a particular tumblr at once, type /archive after the tumblr name eg http://afterthetorchlight.tumblr.com/archive ).

Finally! One tumblr I occasionally look at, apparently belonging to a young woman in Sweden, is http://tankgirlsinspiration.tumblr.com/archive . I realized just now that the page name she’s now using for her tumblr is… Mathilda Lando. And her bio is Mathilda’s. Have a look at her page – I think it’s fairly typical of a certain type of tumblr – a curious mixture of photos of herself, celebrities, fashion, cute things, animals and hardcore pornography. I’ve posted the link to her archive view; to see any individual post, just click on it. Or, to see it as she’d like you to see it, click here.

Again: I think I’ve made it clear by now that many tumblrs contain hardcore pornography: if this offends you, there are plenty of other places to visit on the net. Or so I’m told.

Thanks for joining me on another weird meander! If you see me at Bouchercon, and made it this far, hit me up and I’ll buy you a drink! In the meantime, what are your prognostications of current films that will be cult hits down the road? Any personal favourites?