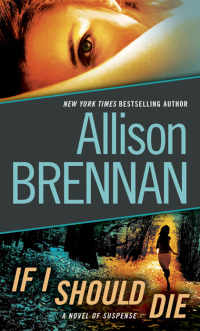

I’m deep into reading the page proofs for IF I SHOULD DIE, book three in the Lucy Kincaid series. I really love this final stage of the publication process–at least the final stage on my end. I see the book as it’s going to be printed. It’s the last time I can make changes–ensuring the copyedit changes were made correctly, double checking the timeline, tweaking words and phrases. No major changes can be made at this point, but I often find the little errors–repetitive words or phrases, for example.

I also read most of my book out loud during this final stage, so it takes me longer to go through the proofs than most authors. Reading out loud helps me make sure the rhythm is right, especially in dialogue. To me, an author’s voice has as much to do with the rhythm of the story as with anything else. It has to feel right, or I’ll tweak it. There’s nothing I can explain or map out–I just know my rhythm is off when the story doesn’t sound right. It’s ironic, because I’m a very visual storyteller–meaning, I *see* the story unfold, I don’t hear it. I write what my POV character sees and feels. When I revise, I’m looking for for the visual story structure. But this final stage is all about story rhythm.

Which made me think about all the writing guidelines and story structure. I’m a big fan of Christopher Vogler, and have a well-worn copy of THE WRITER’S JOURNEY. I’ve never used the hero’s journey to plot or structure a novel, but I have see the hero’s journey in all my books … after the fact. So I can identify when my protagonist crosses the threshold. I know when I hit the midpoint of the story–and at that point whether my book is on the long or short side. Once I hit the third act, I feel the momentum of the story.

When I read the book in its near-final form, I see all that laid out, and it feels almost magical because I didn’t plan it that way. I remember when I first read Vogler. I had already sold my first book, and someone recommended it to me. I was reading it while doing stress tests during my last pregnancy–one hour of doing basically nothing. I saw how my debut novel followed the hero’s journey and it stunned me. But it shouldn’t, because in the introduction Vogler says:

“All stories consist of a few common structural elements found universally in myths, fairy tales, dreams and movies. They are known collectively as The Hero’s Journey.” He goes on to quote Joseph Campbell who “exposed for the first time the pattern that lies behind every story ever told.” And the key for me, that “all storytelling, consciously or not, follows the ancient patterns of myth. … The way stations of the Hero’s Journey emerge naturally even when the writer is unaware of them.”

I believe this is true, whether you plot or don’t plot; whether you consciously assess the hero’s journey as you write or don’t see it until the end of the story.

That’s why I love the final page proofs. I can see the structure of my story clearly for the first time, and each and every book follows the hero’s journey. Not rigidly–because the hero’s journey is as flexible and diverse as people. It’s not a formula, but a guideline into the human psyche in how we perceive stories. And that’s why it always marvels me that the hero’s journey is always there at the end.

But the steps of the journey are not the only “tests” of whether a book is good or not. Sol Stein wrote that the first page was the most important. If a reader picks up a book in the bookstore, reads the first page, then turns the page, they are more likely to buy the book. If they don’t turn the page, they almost always put the book back on the shelf.

Agent Noah Lukeman has a writing book called THE FIRST FIVE PAGES–and you guessed it, he claims they are the most important in any book. Many agents and editors say they know whether a book is good after the first five pages. Some give the author more time if the writing is there, but many don’t go beyond the beginning.

The Campaign for the American Reader has the “Page 69” test. They quote from John Sutherland’s HOW TO READ A NOVEL:

“Marshall McLuhan, the guru of The Gutenberg Galaxy (1962), recommends that the browser turn to page 69 of any book and read it. If you like that page, buy the book. It works. Rule One, then: browse powerfully and read page 69.”

There’s also the midpoint of the book. For me, the midpoint is just as important as the turning points at the end of each “act.” Some claim that at the midpoint, the protagonist hits rock bottom (or near rock bottom) where it doesn’t seem like it can get any worse, or a false victory, where everything seems to be going great (but of course, it’s not.) In police procedures, the midpoint is often where the protagonist thinks they’ve figured out the crime, identified the suspect, made an arrest, and all is right in the world. Case closed … then right after something happens and she releases she has NOTHING, and is worse off than at the beginning.

Of course, there are infinite variations and ideas for the midpoint–like one main character is at the all-time high, while the other is at the all-time low.

And then there are the readers who have to read the end of the book FIRST. (Yes, I know some of these insane people, they drive me crazy. But there are more of them out there than you think!)

All these “tests” — first lines, first pages, page 69, the midpoint, the ending — are supposed to help the reader decide whether they should read the book.

Ironically, I don’t use any of them.

When writing this blog, I looked at the “tests” in my proofs for IF I SHOULD DIE. The midpoint is critical–during the midpoint chapter, my hero Sean Rogan learns some important information about the villain, but he doesn’t know how it all fits. At the end of the chapter, he gets a warning from an unknown source (who may be a good guy or a bad guy or neutral) that the bad guys know what flight his girlfriend, Lucy Kincaid, is going to be on. That tip completely changes their plans and sets into motion a series of events that go from bad to worse.

All my midpoints tend to have story changing elements. In my debut novel THE PREY, one of the main characters is murdered and that changes the motivation of the hero. In SEE NO EVIL, the prime suspect ends up dead.

The Page 69 test in DIE gives the reader part of a barroom conversation that offers up more questions for my hero and heroine than answers. My first three pages are the prologue which is one of the creepiest prologues I’ve written–a guy treks into an abandoned mine to visit the frozen body of the woman he loves. Chapter One begins with Sean and Lucy in bed right after morning sex while on vacation in the Adirondack mountains when they smell smoke. I remember in my first draft, it took six or seven pages to get to the smoke, and I knew as soon as I started editing that it was way too long–even though the six pages were interesting, there was no action. By the end of page two, we know that Sean’s helping a family friend who has been the victim of sabotage while getting a new resort ready to open, that this isn’t supposed to be a big case because Sean and Lucy are expecting to enjoy a well-deserved vacation before Lucy starts her training at Quantico. And then–well, it definitely doesn’t go as planned. 🙂

Apply one of these tests to a book you’re reading now and share with us–avoiding spoilers if possible (or at least identify them!)