Related posts:

Related posts:

I don’t care what the plan is as long as we have one.

– Kevin Bacon in Tremors

I was teaching last weekend, another one of my patented how-to-use-film-techniques-to–craft-a-killer-novel in one impossible hour workshops, and I found myself focusing on a plot element that I haven’t spent all that much time talking about here, so I thought I’d blog about that today.

You always hear that “Drama is conflict”, but when you think about it – what the hell does that mean, practically?

It’s actually much more true, and specific, to say that drama is the constant clashing of a hero/ine’s PLAN and an antagonist’s, or several antagonist’s, PLANS.

(Oh, you thought this blog was going to be about life plans? Hah. Like I have a clue.)

In the first act of a story, the hero/ine is introduced, and that hero/ine either has or quickly develops a DESIRE. She might have a PROBLEM that needs to be solved, or someone or something she WANTS, or a bad situation that she needs to get out of, pronto.

Her reaction to that problem or situation is to formulate a PLAN, even if that plan is vague or even completely subconscious. But somewhere in there, there is a plan, and storytelling is usually easier if you have the hero/ine or someone else (maybe you, the author) state that plan clearly, so the audience or reader knows exactly what the expectation is.

When in JAWS, Sheriff Brody is confronted with the problem of a great white shark eating people in his backyard (ocean), his initial PLAN is to close the beach to swimmers. He throws together some handmade “Beaches Closed” signs and sticks them in the sand. Problem solved, right?

Yeah, right.

If that initial plan had actually worked, JAWS wouldn’t have made a hundred zillion dollars worldwide, not to mention cinematic history. The whole point of drama (including comedy) is that the hero/ine’s plan is constantly being thwarted: by the main antagonist, by any number of secondary and tertiary opponents, by the love interest, by the weather, or by the hero/ine him or herself (because you know we’re all our own worst enemies.).

So almost always, the initial plan fails. Or if it seems to succeed, it’s only to trick us for a moment before we realize how wretchedly the plan has failed. That weak initial effort is because it’s human nature to expend the least effort possible to get what we want, and only take greater and more desperate measures if we are forced to.

Now, in JAWS, the primary antagonist is the shark. The shark’s PLAN is to eat. Not just people, but whatever. (Interestingly, that plan seems to evolve…)

Brody’s initial plan of closing the beaches might actually have solved his problem with the shark, because without a steady supply of food, the beast probably would have moved on to another beach with a better food supply.

But Brody’s initial plan brings out a secondary antagonist: the town fathers, led by the mayor (and with a nice performance by co-screenwriter Carl Gottleib). They don’t want the beaches closed, because the summer months, particularly the fourth of July weekend, represents 70 percent of the town’s yearly income. So the town fathers obliquely threaten new sheriff Brody with the loss of his job if he closes the beaches, and Brody capitulates.

This proves disastrous and tragic, as the very next day (as Brody watches the water from the beach, as if that’s going to prevent a shark attack) another swimmer, a little boy, is killed by the shark, practicing its plan.

The town fathers hold a town meeting and decide on a new plan: they will close the beaches for 24 hours. Brody disagrees, but is overruled. Eccentric captain Quint offers his services to kill the shark – for 10 grand. The town fathers are unwilling to pay.

In response, Brody develops a new plan, one we see often in stories: he contacts an expert from afar, oceanographer Matt Hooper, a shark specialist, to come in and give expert advice.

Meanwhile a new antagonist, the mother of the slain little boy, announces a plan of her own: she offers a bounty for any fisherman who kills the shark who killed her son.

The bounty brings on a regatta of fishermen from up and down the eastern seaboard. One of these crews captures a tiger shark, which the mayor is quick to declare the killer shark. Case closed, problem solved, and the beaches can be reopened. Hooper is adamant that the shark is far too little to have caused the damage done to the first victim, and wants to cut the shark open. The mayor refuses, and is equally adamant that there is no more need for Hooper. We see Brody agrees with Hooper, but wants to believe that the nightmare is over. However, when the dead boy’s mother slaps Brody and accuses him of causing her son’s death (by not closing the beaches), Brody agrees to investigate further with Hooper, and they cut the shark open themselves to check for body parts. Of course, it’s the wrong shark.

Brody’s revised plan is to talk the Mayor into closing the beaches, but the Mayor refuses again, and goes on with his plan to reopen the beaches (and highly publicize the capture of the “killer” shark).

The beaches reopen for 4th of July and the town fathers’ failsafe plan is to post the Coast Guard out in the ocean to watch, just in case. While everyone is distracted by a false shark scare, the real shark glides into a supposedly secure cove where Brody’s own son is swimming, and kills a man and nearly kills Brody’s son. (And it’s so diabolical in timing that it almost seems the shark has a new plan of its own – to taunt Brody).

At that point the Mayor’s plan changes – he writes a check for Quint and gives it to Brody, to hire the captain to kill the shark. But that’s not enough for Brody, now. He needs to go out on the boat with Quint and Hooper himself, despite his fear of the water, to make sure this shark gets dead.

This happens at the story’s MIDPOINT, and it’s a radical revamp of Brody’s initial plan (which always included avoiding going in the water himself, at all cost). And it’s very often the case that at the midpoint of a story, the initial PLAN is completely shattered (a great example is in THE UNTOUCHABLES, which I’ve talked about here:

And yet, Brody is still not ultimately committed. For the next half of the second act, he allows first Quint and then Hooper to take the lead on the shark hunt. Quint’s plan is to shoot harpoons connected to floating barrels into the shark and force it to the surface, where they can harpoon it to death. But the shark proves far stronger than anyone expected, and keeps submerging, even with barrel after barrel attached to its hide.

And now a truly interesting thing happens. The shark, supposedly a dumb beast, starts to do crafty things like hide under the boat so the men think they’ve lost it. It seems to have a new, intelligent plan of its own. And when the men’s defenses are down, the shark suddenly batters into the ship and breaks a hole in the hull, causing the boat to take on alarming quantities of water, and making the men vulnerable to attack.

Brody’s plan at that point is to radio for help and get the hell off the boat. But in the midst of the chaos Quint suddenly turns into an opponent himself by smashing the radio – he intends to kill this shark.

Hooper takes over now and proposes a new plan: he wants to go down in a shark cage to fire a poison gun at the shark. But the shark attacks the cage, and then as the boat continues to sink, the shark leaps half onto the deck and eats Quint.

Brody is now on his own against the shark, and in one last, desperate Hail Mary plan (the most exciting kind in a climax), he shoves an oxygen tank into the shark’s jaws and then fires at the shark until the tank explodes, and the shark goes up in bloody bits. As almost always, it is only that last ditch plan, in which the hero/ine faces the antagonist completely on his or her own, that saves the day.

I hope this little exercise gives you an idea of how it can be really enlightening and useful to focus on and track just the plans of all the main characters in a story and how they clash and conflict. If you find your own plot sagging, especially in that long middle section, try identifying and tracking the various plans of your characters. It might be just what you need to pull your story into new and much more exciting alignment.

And of course the question is: any favorite examples of plans for me, today?

Related posts:

————————————————————————————————————-

And….

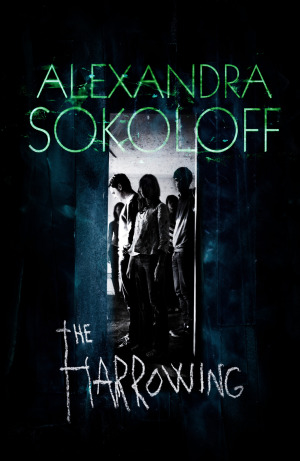

I am thrilled to announce that the The Harrowing finally gets its U.K. release this Thursday, September 17, with this fab new cover, one of my favorites – I guess I mean favourites – ever:

“Absolutely gripping…It is easy to imagine this as a film…Once started, you won’t want to stop reading.”

– The London Times

I find myself now, for various reasons, in a sort of therapy (is that vague enough? Because I can easily be more vague…) which requires that I regularly talk about my thoughts and feelings, and things like How I Am.

Some of you who have met me in person have noticed and called me on the fact that I rarely talk much about myself – I’m very good at turning the conversation to YOU so that I don’t have to disclose anything. (Or maybe more because I have no idea How I Am. Remember, I started blogging about story structure primarily so I wouldn’t have to talk about myself anymore… and anyway if I’m at a conference the answer is always the same – I’m deliriously happy. Who wouldn’t be?)

To a certain extent all writers are good at this, turning the conversation onto someone else, because hey, it’s character research. Maybe in fact all good writers are good at it, and only the annoying ones that you would never read anyway talk about themselves all the time (and I know you all know who I mean).

But in this therapy I am very good at talking about myself. I disclose all kinds of things. I even cry. Because I am nothing if not a good student, expert at discerning what a teacher (or director or choreographer) wants from me.

When I was doing improv I had directors who called personal disclosures like the ones I am now engaged in “California Scenes”. It wasn’t a compliment. A California scene is when you just dump every sordid detail of your character’s life onto your scene partner – and never actually tell the real truth.

The thing is, what truth? What real?

What I mean is, how do I know what’s me when I just spent four hours in what was basically a dissociative state as a sixteen-year old girl tracking a potential mass murderer through the back tunnels of a shopping mall? I can tell you her feelings, but those aren’t really my feelings. Except that for the last four hours, they were.

When you spend most of your waking day being someone else, and most of the rest of it dreaming, who are you really?

This is I think why, for so long, actors were shunned by society and not allowed to be buried in hallowed ground. (That I suppose and all that unhallowed sex). Because they’re not really real. You never know who they are. But then what about us writers who play EVERY part, constantly, plus sometimes an omniscient narrator on top of that? How much less real does that make us?

When I and my siblings were in high school, my brother once brought home a Cosmo magazine with one of those great Cosmo quizzes (you know you all love them): Are you a Chameleon or a True Blue? And said to my sister and me: “Right there is the problem. I’m a True Blue and you two are Chameleons.” And okay, yeah, we didn’t even have to take the quiz to know that he was right. But we did take the quiz, and he was right.

Day to day I’m actually quite fine with my Chameleon nature, because it IS who I am. But I’m less comfortable with it in therapy; it makes me feel like I’m lying. Maybe because in the group I seem to be surrounded by True Blues. But maybe those people have a very strong sense of who I am, and I’m the one who doesn’t.

Now, we all write ourselves as characters, to a certain extent or another. I certainly am not as much any character I’ve written as Cornelia is Madeleine Dare, not even in the same universe, but I can point to certain characters in certain books and say definitively that they’re more me than others. I’ve noticed our readers play that game, too (just the other day someone here commented that she sees Tess when she reads Maura Isles, and really, who doesn’t?). Only at least with me, they’re mostly wrong. People think I’m Laurel MacDonald because there are places in THE UNSEEN where she says things in my voice, and I used a lot of my California-to-North Carolina experience in the book. But she’s a lot prettier than I am and also worlds less sure of herself… she’s softer, so much so that I don’t much relate to her. I’ve also had people say to me, “Do you know someone like Robin (in THE HARROWING)? Because she seems so real but you’re not at all like her.” But actually I am very much like her, but that’s just one half of me, and the other half, that masks her, is another character in the book.

I am very grateful for the conference circuit, which for me provides a very grounding, real-life balance to the all that writing and dissociation I do. I can find myself again in large groups of people (well, especially if there’s dancing), and when I am forced to talk about myself (on panels, etc.), I remember who I am, apart from the random dreamlike state that writing is.

But I guess this is what is puzzling me. Are ALL writers Chameleons, or are some of us True Blues who easily snap back into our “real” selves once we turn off the computer for the day? Are some people with “real” jobs as much Chameleons as actors or writers, playing a completely different part or parts during the day, at work, which parts are as much a dissociative state as writing?

What do you think? Are you a Chameleon or a True Blue?

And for bonus points, writers: which characters that you’ve written are most like you? Readers, which characters do YOU think are most like the authors who write them? And most importantly, why do you think actors were not allowed to be buried in hallowed ground?

– Alex

—————————————————————————————

Alex will be in New Orleans this Labor Day weekend for Heather Graham’s unmissable Writers for New Orleans Conference, teaching Screenwriting Tricks for Authors, paneling, and (thank God) being herself by playing a pirate wench and riverboat prostitute with Heather’s Slush Pile Players. Pitch sessions available with editors and publishers Leslie Wainger, Adam Wilson, Eric Raab, Ali deGray, Kate Duffy and Helen Rosburg.

WARNING: there are SPOILERS everywhere in this post, so I am providing an up-front list of the books and movies I discuss, so if you haven’t read or seen some of them and would like to, unspoiled, you may want to proceed cautiously.

Presumed Innocent

The Others

Oedipus (but honestly, if you don’t know that one…)

Chinatown

The Sixth Sense

The Crying Game

Seven

A Kiss Before Dying

Fight Club

Identity

The Eyes of Laura Mars

Psycho

Don’t Look Now

In Bruges

Boxing Helena

Open Your Eyes (Abre Los Ojos)

Falling Angel

Angel Heart

The Murder of Roger Ackroyd

No Way Out

Eastern Promises

As mystery and thriller authors, designing story twists is a regular part of our job. After all, we don’t want our readers to guess the identity of our killers before our detectives do! We employ classic story tricks… I mean, literary devices… like red herrings, misdirection, false leads, false alibis, plants and payoffs, irony and unreliable narrators, to keep our readers (or viewers) guessing.

If you’re interested in building your skill at twisting a story, I (as always) advocate making a list (ten at least!) of stories that have twists that you really respond to, and analyzing how the author, screenwriter, or playwright is manipulating you to give that twist its power, so that you can do the same for your readers and viewers.

I also think it’s helpful to realize that these techniques have been around since the beginning of drama, or I’m sure really since the cave-dweller storytellers (“The mastodon did it!”). Knowing the names of techniques is always of use to me, anyway!

And I’d also like to note up front that big twists almost always occur at the act climaxes of a story, because a reveal this big will naturally spin the story in a whole other direction. (If you need more explanation about Act Climaxes and Turning Points, read here.)

Let’s break down some different kinds of twists.

* ANAGNORISIS

The Greeks called twists and reveals Anagnorisis, which means “discovery”: the protagonist’s sudden recognition of their own or another character’s true identity or nature, or realization of the true nature of a situation.

This is always a great thing if you can pull it off about the protagonist, because we kind of expect to find out unexpected things about other people, or have surprises come up in a situation, but to find out something you never suspected about yourself is generally a life-altering shock.

So here’s a big twist that has worked over and over again:

* THE PROTAGONIST IS THE KILLER (or criminal), BUT DOESN’T KNOW IT

– We find probably the most famous twist endings of world literature in Sophocles’ OEDIPUS THE KING (429 BCE) in which Oedipus, the king of Thebes, is trying to discover the cause of a devastating plague in the city, only to find that he himself is the culprit, cursed by the gods for killing his father and marrying his own mother.

– I’ve talked at length about the influence of Oedipus on the Polanski/Towne classic film CHINATOWN (discussion here).

– But the noir mystery FALLING ANGEL, by William Hjortsberg, and Alan Parker’s movie adaptation of that book, ANGEL HEART, steals its twists from Oedipus as well: PI Harry Angel is hired by Louis Cyphre to find Johnny Favorite, who owes Cyphre (his soul, turns out!). Angel finds out he himself is the man he’s looking for, Johnny Favorite, and also that he’s slept with and killed his own daughter.

– PRESUMED INNOCENT (book and film) is another take on the Oedipal detective story, in which main character and detective (by dint of being a ADA) Rusty Savage is guilty, not of the murder of his mistress, but of infidelity, so he protects his wife, the real killer, from detection.

PRESUMED INNOCENT also employs a great bit of misdirection, in that the victim was sadomasochistically bound and apparently sexually tortured and raped – there was semen found inside her. So even though the cheated wife would ordinarily be the prime suspect, we and all authorities rule her out.

* THE UNRELIABLE NARRATOR

Another literary device that makes for a powerful twist is the unreliable narrator.

– Agatha Christie surprised and therefore irked some critics with this one in THE MURDER OF ROGER ACKROYD.

– THE USUAL SUSPECTS has won classic status for its now famous reveal that meek Verbal Kint is the nefarious Keyser Soze he’s been talking to the police about, using random objects in the police station to add details to his fabricated story.

– FIGHT CLUB puts a spin on the unreliable narrator, as antagonist Tyler Durden is revealed to be an alter ego of split-personality narrator Edward Norton (called just “The Narrator”, which is a sly little hint of the device being used.)

– Of course multiple personality disorder can be used as a twist all on its own, most famously employed in PSYCHO, but also in, hmm, let’s see… THE EYES OF LAURA MARS, and dozens of cheesy ripoffs of the concept (fascinated as I am by MPD, this is one device I’m not sure I’d ever want to tackle, myself).

– The 2003 movie IDENTITY takes the MPD twist several steps further: EVERY character in the movie a different aspect of John Cusack’s fractured personality.

* KILL OFF AN IMPORTANT CHARACTER UNEXPECTEDLY

– While I’m thinking about it, PSYCHO has another famous twist, which I’m sure at the time of the film’s release was just about as shocking as the reveal of “Mother”: the apparent main character, Janet Leigh, is murdered (spectacularly) at the first act climax.

– This was copied much less effectively but still successfully in the 1987 thriller NO WAY OUT, in which the apparent love interest dies at the first act climax.

– The Brian DePalma film THE UNTOUCHABLES kills off a beloved sidekick (the Charles Martin Smith character) at the Midpoint, and as I recall I didn’t see that one coming at all (until he got into the elevator, that is…)

* THE “BIG SECRET”

The big secret reveal, done well, means a pretty guaranteed sale and often gonzo box office. Some famous examples:

– THE SIXTH SENSE. We all know this one: the child psychiatrist who seems to be treating a little boy who claims to see dead people turns out to be – one of the dead people the boy is seeing. This one is especially interesting to note because writer/director M. Night Shyamalan went through several drafts of the script before he realized that the Bruce Willis character should be a ghost. Which goes to prove you don’t have to have a great twist planned from the very beginning of your writing process – you can discover a perfect twist in the writing of the story.

– THE OTHERS takes a page from SIXTH SENSE and triples it: they’re ALL dead. A young mother and her two light-sensitive children think their creepy old house is haunted. A climactic séance reveals that actually the mother has shot herself and the children and THEY’RE the ones haunting the new family in the house.

– THE CRYING GAME’s famous twist reveals gorgeous, sexy Dil, whom we have fallen in love with just as surely as main character Fergus has, is a man. That was a twist that hit squarely below the belt, as writer/director Neil Jordan forced us to question our own sexuality as well as our concepts about gender.

THE CRYING GAME has a couple of earlier twists at the first act climax, too: IRA soldier Fergus becomes more and more sympathetic to his personable hostage Jody, enough so that Fergus lets Jody run free when he takes him out in the forest to execute him. We kind of saw that one coming. But then there’s a horrifying shock when on his run to freedom Jody is suddenly hit and killed by a truck. Devastating, and totally unexpected.

– EASTERN PROMISES. In one of the most emotionally wrenching reveals I’ve seen in a long time, Viggo Mortensen, the on-his-way-up chauffeur for a prominent leader of the Russian mob, turns out to be a Scotland Yard agent so deep undercover that in the end he is able to take over the whole mo

b operation – but must give up Naomi Watts in the process. A wonderful “love or duty” choice, which you don’t see often, these days. And if that isn’t enough to convince you to see the film, try: Viggo. Naked and tattooed. In a bathhouse. For a five-minute long fight scene. Did I mention he’s naked?

– We see another great reveal about the nature of a protagonist in BLADERUNNER: Harrison Ford, the replicant hunter Deckard, is himself a replicant.

* IRONY

Actually this whole post was inspired by my recent structure breakdown of THE MIST, the film, which takes the idea of its shocker ending from a line in King’s original novella, but gives it an ironic twist that is pure horror: After battling these terrifying creatures for the whole length of the movie, our heroes run out of gas and the protagonist uses the last four bullets in their gun to kill all his companions, including his son (with the agreement of the other adults). And as he stumbles out of the car intending to meet his own death by monster, the mist starts to lift and he sees Army vehicles coming to the rescue. People loved it, people hated it, but it was one of the most devastating and shocking endings I’ve seen it years.

* OTHER COMMON PLOT TWISTS:

Here are several twists that we’ve all seen often:

– The “S/he’s not really dead” twist – as in BODY HEAT (and overused in ten zillion low- budget horror movies).

– The “It was all a dream” twist: OPEN YOUR EYES, BOXING HELENA (I’m not sure what you’d have to do to make that one play, it’s so universally loathed.)

– The “ally who turns out to be an enemy” twist: as in John Connolly’s EVERY DEAD THING, William Goldman’s MARATHON MAN,

– And the “enemy who turns out to be an ally” twist: Captain Renault in CASABLANCA, Professor Snape in the first Harry Potter (and then reversed again later…)

* JUST BE ORIGINAL

A twist doesn’t have to be as cataclysmic as a “big secret” reveal. Sometimes a plot element or action is so unexpected or original that it works as a twist.

– I was watching THE BIG HEAT the other night, shamefully had never seen it, and there are several big surprises. I knew that too-good-to-be-true wife was going to die, but I was totally unnerved by villain Lee Marvin throwing a pot of scalding coffee in girlfriend Gloria Grahame’s face. Although you don’t actually see the burning, that brutality must have made people jump our of their seats in 1953. Then (although she’s one of my favorite actresses of all time and totally up to the task) I was equally shocked to see Grahame’s character take over the movie from hero Glenn Ford (kudos to writer Sydney Boehme and director Fritz Lang for that) and shoot another woman (a co-conspirator of Marvin’s) so that key evidence will be revealed, then go after Marvin herself and burn him in exactly the way he burned her (before he shoots and kills her).

What works as a twist there is the sudden primacy of a seemingly minor character – especially a woman who would normally just be there for eye candy. Sad to say, but portraying a female character who is as interesting as women actually are in real life still counts as a standout.

– In the movie SEVEN there’s a great twist in the second act climax when John Doe, the serial killer the two detectives have been pursuing, walks into the police station and turns himself in. You know he’s up to no good, here, because it’s Kevin Spacey, but you have no idea where the story is going to go next.

And of course then you have that ending: that John Doe has always intended himself as one of the seven victims (his sin is “envy”), and the infamous “head in the box” scene, as Doe has a package delivered to Brad Pitt containing the head of his wife so that Pitt will kill Doe in anger.

Hmm, can’t end this post with that example – too depressing.

– Okay, here’s a favorite of mine, for sheer trippiness: Donald Sutherland being killed by a knife-wielding dwarf in DON’T LOOK NOW – and the delightful homage to the scene in last year’s IN BRUGES.

And the above are not even scratching the surface of great plot twists – I could really write a book.

So, everyone, what are some of your favorite movie and book plot twists? Writers, do you consciously engineer plot twists? And editors (if Neil isn’t in the Hamptons this weekend…), on the level – are you more likely to buy a book that has a big twist?

– Alex

Related posts:

What are Act Breaks, Turning Points, Act Climaxes, Plot Points?

Just returned from crazy breakneck weekend – Thrillerfest in NY, and ALA in Chicago. Because I’m a Pisces I have this idea that I can be two places simultaneously. It doesn’t quite work that way. Or anyway, there’s always a price.

At TFest, as some of you know, my story “The Edge of Seventeen” from THE DARKER MASK anthology won the Thriller award for Best Short Fiction!

Here’s the complete list of winners:

ThrillerMaster Award: David Morrell

In recognition of his vast body of work and influence in the field of literature

Silver Bullet Award: Brad Meltzer

For contributions to the advancement of literacy

Silver Bullet Corporate Award: Dollar General Literacy Foundation

For longstanding support of literacy and education

Best Thriller of the Year:

THE BODIES LEFT BEHIND by Jeffery Deaver (Simon & Schuster)

Best First Novel:

CHILD 44 by Tom Rob Smith (Grand Central Publishing)

Best Short Story:

THE EDGE OF SEVENTEEN by Alexandra Sokoloff (in Darker Mask)

And yes, I was very happy to be the estrogen in the lineup. Actually I tend to do my best in situations of complete gender imbalance.

Then I went straight on (well, one missed flight later) to do signings at ALA, the American Library Association conference in Chicago, which apparently had an attendance of 27,000 people. Which was far more than anyone had anticipated and is great news for all of us bookish types.

And I have to say Chicago was as beautiful as I’ve ever seen it, ever – absolutely stunning weather, which I don’t think I’ve ever been able to say about Chicago before. I could almost have been lulled into living there if I didn’t know what happens around November. Or in July, for that matter.

I took that riverboat architecture tour with my friends and Sisters in Crime sisters Doris Ann Norris and Mary Boone, and it really is the best thing about these conferences – being able to get these fast but incredibly layered snapshots of different cities. I love it.

Now I’m headed into a couple of weeks of signings and interviews (including North Carolina Bookwatch, a really big deal in that state) while doing revisions on BOOK OF SHADOWS, and at the same time I have to sort out everything that happened and didn’t happen during my move, which is another story entirely, and, oh yeah, get back to blogging.

Not much that looks like vacation there, right? But instead of feeling exhausted, I feel rejuvenated, and realigned. Conferences are really good for the Big Picture. Going to the same conference for several years in a row is especially great because you can see your career on a continuum. I wasn’t even published when I went to my first Thrillerfest. Now, my fourth year there, I know what to do with the people I meet and the opportunities that come up. I’m much more aware of what a conversation can lead to and how to take advantage of that (I know, it sounds like I’m talking about something else. Of course that potential is always there, too.).

Opportunities abound at conferences – I really do feel that everyone you could possibly need to talk to at a particular moment in time is at whatever conference you are at. That’s always been true for me, even when I had no idea what I was doing. Now that I have a bit of an idea what I’m doing it’s even more true. Example: I have been needing to ask a lot of precise, technical questions about the whole Amazon/Kindle publishing thing. So I’m standing around in the Hyatt lobby catching up with friends and Daniel Slater, the very guy in charge of all that, walks right up to us and introduces himself.

That’s not an anomaly, it’s what happens dozens or hundreds of times over a few days at a con. It’s like magic, I swear.

Also these days I actually remember who everyone is. Definitely a plus.

Seeing the same group of authors regularly (at a particular conference) gives you a good idea of what people are doing that works, and what is not working so well. There’s always a lot going on that you can’t see, but you do get ideas.

And then there are those moments of sheer inspiration and purpose – like this year’s Thrillermaster David Morrell’s speech at the banquet. He was talking about how we all have a responsibility to bring something new to the genre, to advance the genre, and explained exactly how he had been attempting to do that in several of his books. He also said that every time he sits down with a new project he writes a letter to himself talking about why he wants to spend a year of his life on this particular book. Whoa! Talk about getting in alignment. That is absolutely what they call in yoga “attention and intention”. There is no way not to write a better book if you have done that.

I’m telling you, a graduate course in writing in 15 minutes.

ALA, now, is scary for the sheer numbers of books. The “Why didn’t I write that?” quotient is high. Also the sheer number of books by some individual authors is beyond scary. The “Why didn’t I start sooner?” question can tear you apart.

The fact is, I’ve just finished revisions on my fourth book. I’m a complete novice comparatively. And I understand better than ever why a lot of readers hold authors in awe (I just finished Michael Connelly’s SCARECROW and I swear I was holding my breath through whole parts of it. How the HELL does he DO that?). But also, all of those books come out of those people, people we know. People we are. The more books out of an author the more you have to marvel that one little 120 or 220 pound person can make all that happen, all those characters and worlds. The power of that! It’s mind-bending.

But here I was, this weekend, surrounded by authors – who have dozens, if not hundreds of books to their name, and I was wondering how many books I’m going to have to have out before I feel any kind of comfort level. In fact, I wonder if there ever IS a comfort level – if Tess and Allison experienced a moment (a certain number of books, the first or second time on the NYT list) that they said: “Ah, yes. I’m here.” (I mean, even temporarily!)

At the moment, for me four still feels really scant, which is maybe ridiculous, since every completed book is a bloody miracle. But I think that that impatience and dissatisfaction, of “not enoughness”, is typical of not just authors, but artists in general. It’s what drives us to produce more. I love that Aristotle called artists “productive philosophers”. That’s what we do – we produce. Art is philosophy, I believe that, but it is also so concrete. We need to see, touch, feel what we do. We need to have other people be able to see, touch, feel it.

Which is good to remember because now, despite a pretty full promotional schedule, I’m going to be doing a huge amount of writing. One project, the Screenwriting Tricks for Authors book, is very near finished. I have two more that I need to put in proposal form, and a third I should be thinking about. At the beginning of an idea, all that chaotic newness and possibility, it’s good to remember that it will be a concrete product at the end: a book.

And I just put one away, for the time being. Maybe for a month, maybe for longer. I haven’t done that with a project in a while, but I think it’s the right thing to do, for reasons I can’t even articulate at the moment, but I think I’m doing the right thing. One thing about having a small number of books out is that you want to maintain a certain focus. Especially when you’re writing standalones.

There’s nothing like a conference for putting your priorities in order. Out of all that chaos, you come away with clarity.

So I’d love to get other reports. Those of you who were at Thrillerfest or ALA, or RWA (going on right now!), what did you come away with that you can share with us?

And everyone else – will you tell us some great thing you learned or experienced at a conference?

And has anyone here EVER experienced that “Ah, yes. I’m here.” moment?

– Alex

One of the things that you hear ad nauseum in Hollywood story meetings is: “And I think Seattle (Rome, San Francisco, New York, L.A., Akron) should be a character in this movie!”

Not that it’s a bad note (although it’s funny how you can predict who will say it, and how you, the writer, must always pretend that it’s the most brilliant and startling idea you’ve ever heard). It’s just that to me this is so obvious I don’t know why anyone would ever have to bring it up. It’s like saying your story needs a plot.

Of course the location is a character.

This is excruciatingly crucial when, like I do, you write on the supernatural side, and it must seem that the very land and/or city, and/or house (or in my current WIP, boat), and elements are conspiring against the human characters. There are vast forces at work, and they have their own intelligence.

But it’s not just in my genre. I think one of the key promises of a novel, any novel, any genre, is that it takes you, the reader, away from wherever you are. That’s one of the main reasons we read, isn’t it? And even when you, the writer, are writing the darkest of dark stories – set in a prison, or in the middle of war, or an impoverished country, or a supernatural dystopia, your reader, for whatever twisted reason, is picking up that book to BE THERE. And it is one of your non-negotiable jobs as an author, or filmmaker, to take them there – completely out of their own body, their own house, their own city, their own reality, and into yours.

“Yours” being the operative word, here, because it’s not enough to say that the story is set in Boston and leave it at that. It has to be your Boston, or your character’s Boston.

“What is it about Boston for you?” a friend asked me recently, as I just finished another book set there.

It’s true, Boston is one of MY cities. Along with London, San Francisco, Berkeley, and Death Valley. Well, that’s not a city. But you know.

My friend really asked the key question, the question every writer should always ask her or himself about the location of his or her story: “What is it about Boston (or whatever) for you?”

Boston is one of those places that I fell in love with the instant I landed in it. It is so twisted, Boston – literally and figuratively… the streets were built along meandering cow paths. They make no sense at all. You round a corner and you could be anywhere. Or anytime.

And then all of that history – the cradle of the Revolution! – and intellect, and literature, and music, and art, and cathedrals, and witches.

Aha. That’s a lot of my personal take about Boston, right there.

For someone like me, obsessed as I am with the devil, Boston is a gold mine. I can write stories about the devil and witches walking around in that city, with the utmost confidence and realism, because they have, and they do.

Here’s another example. Synchronistically, this post turns out to be a great follow up to J.T.’s delicious account of her trip to Napa. Napa is (in spades!) a region with character. It reminds me of the overwhelming influence of the vineyards and wine-tasting imagery that Alexander Payne portrayed to perfection about Central California’s wine country, Sideways. For native Californians, Payne hit every iconic location he could cram into that story; we have all done all of those things, repeatedly (the only thing he left out was the Madonna Inn, which is a whole movie in itself.) The themes of alcoholism and creative inspiration and California excess are pillars of the movie, and the wedding and road trip themes are also completely in line with the mythology of wine country (if I had a dollar for every vineyard wedding I’ve attended… every road trip I’ve taken through Central California… ). And it’s no accident that the characters are a (failed) writer and a (failed) actor – that is mythically Californian. Payne captured the unmistakable character of that region, as well as making it his own. If you want to know what it’s like to live in California, watch that movie.

My new thriller, The Unseen (out this month, for all of you who have been waiting with bated breath) has North Carolina as its character location, and oh, boy, is it a character. Now, I could not have begun to do that story justice from the point of view of a native Southerner – because in case you haven’t noticed, they’re all crazy. 😉

But I could tell it from the point of view of a fish out of water, a Californian transplanted to the South, and experiencing the whole state for the first time. And that point of view I think achieves a quality of isolation and alienation that’s very useful in a supernatural thriller.

Doing my research and being true to the reality of the place was, for me, key. The story is based on real-life experiments done in the Rhine parapsychology lab on the Duke University campus, and I could not have asked for a more Gothic and spooky and atmospheric college to play with. I felt like I was tripping, walking around that school for the first time, it’s that perfect for the book.

The overwhelming forests of North Carolina (I’ve never seen so many trees in my life) were another great atmospheric element. You can hide virtually anything in those damn trees. For a child of the Southern California desert it’s terrifying not to be able to see vistas, and those endless forests are the labyrinth (with all of its mystical implications) that is so much a part of my personal thematic imagery.

Since the story is about a poltergeist house, I had to create a poltergeist house that was absolutely a character in its own right. One that I could know the shape of like I know the lines in my hand – every room and hall and stairway and imprint.

And because writing is magic, I found the absolute perfect haunted mansion: the Weymouth Center, and was actually able to live there for a whole week.

It’s a real haunted house with an awesome backstory; it was one of the “Yankee Playtime Plantations”, the Southern manors that were bought up after the war by newly moneyed Northerners and turned into hunting lodges and sex retreats. I mean, vacation houses. This one was also a hangout for literary lions such as F. Scott Fitzgerald, Thomas Wolfe, Sherwood Anderson, and “editor of genius” Max Perkins.

And oh, you bet that vibe permeates the manor and grounds. The house is not just creatively inspiring in the day and completely terrifying at night… it’s also a total turn-on. My haunting turned much more erotic than I was expecting, because that’s what was actually there in the mansion. Really. It has nothing to do with me.

We are so lucky that as authors our job includes traveling to and

experiencing as many different places as we can get to. Free research! We are even more lucky that so many of the conferences and conventions we attend (Left Coast Crime, Bouchercon, ALA, PLA, World Horror Con, World Fantasy Con, Romantic Times, Romance Writers of America National) “force” us to travel to different cities every year, thus providing whole universes of research with the price of admission. If you’ll take a look, every single one of those cons goes all out to provide field trips specific to the city and area, as well as seminars and field trips by, for example: law enforcement officials who speak about the particular issues they deal with on their turf and famous criminals and crimes of the region; ghost walks through the cities; and tours of the host city’s most interesting features (like the underground street in Seattle at a recent LCC). No matter how overbooked I am at a conference, I never miss the city tours and local law enforcement tracks.

It’s a beautiful system. We can promote our books, meet with our agents and editors, and do all our location research in one weekend.

Because you never know when you’re going to need the character of Denver. Or Phoenix. Or Napa. Or Madison. Or Indianapolis. Or New Orleans. Or the Big Island. Or….

So tell me, ‘Rati writers and readers. What are your favorite cities, or regions? What books and authors portray location as character particularly well? What do you authors do to create the character in your location? Or what convention have you been to that’s given you the best character introduction to a city you’ve ever had?

– Alex

by Alexandra Sokoloff

I’m at Romantic Times this weekend, and in between performing in Heather Graham’s Vampire show, and hot tubs with Barry Eisler and Joe Konrath, I’m teaching that Screenwriting Tricks for Authors workshop. One of the things we did was take several movies in a row and identify the Act Climaxes (plot points, turning points, act breaks, curtain scenes, whatever you want to call them) of each, and I thought I’dpost that here todayso we can look at what all happens at those crucial junctures.

First, a quick review of what each Act Climax does:

Remember, in general, the climax of an act is very, very, very often a SETPIECE SCENE – there’s a dazzling, thematic location, an action or suspense sequence, an intricate set, a crowd scene, even a musical number (as in The Wizard of Oz and, more surprisingly, Jaws.).

Also an act climax is often more a climacticsequencethan a single scene, which is why it sometimes feels hard to pinpoint the exact climax. And sometimes it’s just subjective! These are guidelines, not laws. When you do these analyses, the important thing for your own writing is to identify what you feel the climaxes are and why you think those are pivotal scenes.

Now specifically:

AC T ONE CLIMAX

– (30 minutes into a 2 hour movie, 100 pages into a 400 page book. Adjust proportions according to length of book.)

– We have all the information we need to get and have met all the characters we need to know to understand what the story is going to be about.

– The Central Question is set up – and often is set up by the action of the act climax itself.

– Often propels the hero/ine Across the Threshold and Into The Special World. (Look for a location change, a journey begun).

– May start a TICKING CLOCK (this is early, but it can happen here)

MIDPOINT CLIMAX

– (60 minutes into a 2 hour movie, 200 pages into a 400 page book)

– Is a major shift in the dynamics of the story. Something huge will be revealed; something goes disastrously wrong; s omeone close to the hero/ine dies, intensifying her or his commitment.

– Can also be a huge defeat, which requires a recalculation and a new plan of attack.

– Completely changes the game

– Locks the hero/ine into a situation or action

– Is a point of no return.

– Can be a “now it’s personal” loss

– Can be sex at 60 – the lovers finally get together, only to open up a whole new world of problems

– May start a TICKING CLOCK.

– The Midpoint is not necessarily just one scene – it can be a pro gression of scenes and revelations that include a climactic scene, a complete change of location, a major revelation, a major reversal – all or any combination of the above.

ACT TWO CLIMAX

– (90 minutes into a 2 hour film, 300 pages into a 400 page book)

– Often can be a final revelation before the end game: the knowledge of who the opponent really is.

– Often comes immediately after the “All is Lost” or “Long Dark Night of the Soul” scene – or may itself BE the “All is Lost” scene.

– Answers the Central Question

– Propels us into the final battle.

– May start a TICKING CLOCK

ACT THREE CLIMAX

– (near the very end of the story).

– Is the final battle.

– Hero/ine is forced to confront his or her greatest nightmare.

– Takes place in a thematic Location – often a visual and literal representation of the Hero/ine’s Greatest Nightmare

– We see the protagonist’s character change

– We may see the antagonist’s character change (if any)

– We may see ally/allies’ character changes and/or gaining of desire

– There is possibly a huge final reversal or reveal (twist), or even a whole series of payoffs that you’ve been saving (as in BACK TO THE FUTURE and IT’S A WONDERFUL LIFE)

———— ———————————————–

Okay, for examples, I’m starting today with two of my all-time favorite films, JAWS and SILENCE OF THE LAMBS.

Please feel free to argue my points!

And note all times are APPROXIMATE – I’m a Pisces.

ACT ONE CLIMAX:

JAWS is a 2 hour, 4 minute movie and I would say the first act climax is that big crowd scene 30 minutes in when every greedy fisherman on the East Coast is out there on the water trying to hunt the shark down for the bounty. One team catches a tiger shark and everyone celebrates in relief. Hooper says it’s too little to be the killer shark and wants to cut it open to see if there are body parts inside, but the Mayor refuses. We know that this isn’t the right shark, and we see that Sheriff Brody feels that way as well, but he’s to rn – he wants it to be the right shark so this nightmare will be over. But the real, emotional climax of the act is at the very end of the sequence when Mrs. Kitner strides up to Brody and slaps him, saying that if he’d closed the beaches her son would still be alive. This is the accusation – and truth – that compels Brody to take action in the second act. (34 minutes)

It’s a devastating scene – just as devastating as a shark attack, and a crucial turning point in the story, which is why I’d call it the act climax. Brody is going to have to take action himself instead of rely on the city fathers (in fact, the city fathers have just turned into his opponents).

MIPOINT:

The midpoint climax occurs in a highly suspenseful sequence in which the city officials have refused to shut down the beaches, so Sheriff Brody is out there on the beach keeping watch (as if that’s going to prevent a shark attack!), the Coast Guard is patrolling the ocean – and, almost as if it’s aware of the whole plan, the shark swims into an unguarded harbor, where it attacks a man and for a horrifying moment we think that it has also killed Brody’s son (really it’s only frightened him into near paralysis). It’s a huge climax and adrenaline rush. (This is about 60 minutes and 30 seconds in). Brody’s family has been threatened (“Now it’s PERSONAL”). And as he looks out to s ea, we and he realize that no one’s going to do this for him – he’s going to have to go out there on the water, his greatest fear, and hunt this shark down himself.

ACT TWO CLIMAX

As in the first act climax, here Spielberg goes for a CHARACTER sequence, an EMOTIONAL climax rather than an action one. About 83 minutes into the movie, the three men, Brody, Quint and Hooper, who have been at each other’s throats since they got onto the boat, sit inside the boat’s cabin and drink, and Quint and Hooper start comparing scars – classic male bonding, funny, touching, cathartic. In this midst of this the tone changes completely as Quint reveals his back story, which accounts for his shark obsession: he was on a submarine that got hit during WW II, and most of the men were killed by sharks before they could be rescued. It’s a horrific moment, a complete dramatization of what our FEAR is for these men. And then, improbably, the three guys start to sing, “Show me the way to go home.” (I told you – a musical number!) It’s a wonderful, comic, endearing uplifting, exhilarating moment – and in the middle of it we hear pounding – the shark attacking, hammering the boat. And the men scramble into acti

on, to face the long final confrontation of ACT THREE. (92 minutes in).

ACT THREE CLIMAX –

The whole third act of JAWS is the final battle, and it’s relentless, with Qu int wrecking the radio to prevent help coming, the shark battering a hole in the ship so it begins to sink under them, the horrific death of Quint. The climax of course is water-phobic Brody finding his greatest nightmare coming alive around him: he must face the shark on his own on a sinking ship – he’s barely clinging on to the mast – and blowing it up with the oxygen tank. The survival of Hooper is another emotional climax. (2 hrs. 4 minutes).

The interesting thing to note about JAWS is that despite the fact that it’s an action movie (or arguably, action/horror), every climax is really an EMOTIONAL one, involvin g deep character. I’d say that has a lot to do with why this film is such an enduring classic. . It’s also interesting to consider that in an action movie an emotional moment might always stand out more than yet another action scene, simply by virtue of contrast.

————————————————————————————–

ACT ONE CLIMAX

I’d say it’s a two-parter: The lead-in is the climax of Clarice’s second scene in the prison with Lecter. She’s followed his first clue and discovered the head of Lecter’s former patient, Raspai l, in the storage unit. Lecter says he believes Raspail was Buffalo Bill’s first victim. Clarice realizes, “You know who he is, don’t you?” Lecter says he’ll help her catch Bill, but for a price: He wants a view. And he says she’d better hurry – Bill is hunting right now.

And on that line we cut to Catherine Martin, and we see her knocked out and kidnapped by Bill.

So here we have an excruciating SUSPENSE SCENE (Catherine’s kidnapping); a huge REVELATION: Lecter knows Bill’s identity and is willing to help Clarice get him; we have a massive escalation in STAKES: a new victim is kidnapped; there is a TICKING CLOCK that starts: we know Bill holds his victim for three days before he kills them, and the CENTRAL QUESTION has been set up: Will Clarice be able to get Buffalo Bill’s identity out of Lecter before Bill kills Catherine Martin? (34 minutes in).

MIDPOINT:

The midpoint is the famous “Quid Pro Quo” scene between Clarice and Lecter, in which she bargains personal information to get Lecter’s ins ights into the case. This is a stunning, psychological game of cat-and-mouse between the two: there’s no action involved; it’s all in the writing and the acting. Clarice is on a time clock, here, because Catherine Martin has been kidnapped and Clarice knows they have less than three days now before Buffalo Bill kills her. Clarice goes in at first to offer Lecter what she knows he desires most (because he has STATED his desire, clearly and early on) – a transfer to a Federal prison, away from Dr. Chilton and with a view. Clarice has a file with that offer from Senator Martin – she says – but in reality the offer is a total fake. We don’t know this at the time, but it has been cleverly PLANTED that it’s impossible to fool Lecter (Crawford sends Clarice in to the first interview without telling her what the real purpose is so that Lecter won’t be able to read her). But Clarice has learned and grown enough to fool Lecter – and there’s a great payoff when Lecter later acknowledges that fact.

The deal is not enough for Lecter, though – he demands that Clarice do exactly what her boss, Crawford, has warned her never to do: he wants her to swap personal information for clues – a classic deal-with-the-devil game.

After Clarice confesses painful secrets, Lecter gives her the clue she’s been digging for – he tells her to search for Buffalo Bill through the sex reassignment clinics. And as is so often the case, there is a second climax within the midpoint – the film cuts to the killer in his basement, standing over the pit making a terrified Catherine put lotion on her skin… and as she pleads with him, she sees bloody handprints on the walls of the pit and begins to scream… and just as you think things can’t get any worse, Bill pulls out his T–shirt to make breasts and starts to scream with her. It’s a horrifying curtain and drives home the stakes. (about 55 minutes in)

ACT TWO CLIMAX –

The act two climax here is an entire, excruciating action/suspense/horror sequence: Lecter’s escape from the Tennessee prison, which really needs no description! It’s a stunning TWIST in the action. But it’s worth noting that the heroine is completely absent from this climax. The effect on her is profound, though: She was counting on Lecter to help her catch Buffalo Bill. Now that is not going to happen (the Central Question of the story is thus answered: No.) – it’s a complete REVERSAL and huge DEFEAT (all is lost). Clarice is going to have to rise from the ashes of that defeat to find Bill on her own and save Catherine.

The sequence begins about 1 hour and 12 minutes in and ends 10 minutes later, at 1 hr. 22 minutes.

ACT THREE CLIMAX –

… of course is the long and again, excruciating horror/suspense sequence of Clarice in Buffalo Bill0s basement, on her own stalking and being stalked by a psychotic killer while Catherine, the lamb, is screaming in the pit. This is one of the best examples I know of the heroine’s greatest nightmare coming alive around her in the final battle, and it is immensely cathartic that she wins.

Note that the climaxes in SILENCE OF THE LAMBS are very true to the genre, with elements of suspense, action, thriller and horror. Every single climax delivers on the particular promise of the genre – the scares and adrenaline thrills, but also the psychological game playing.

Okay, so any examples for me today? Or any stories you’re having trouble identifying the climaxes of that we can help with?

– Alex

————————————————————-

Previous articles on story structure: (all also linked at right hand side of blog under WRITING ARTICLES).

Story Structure 101 – The Index Card Method

It’s an interesting thing about blogging – it’s made us able to get a glimpse of hundreds of people’s lives on a moment-by-moment basis. I don’t have a lot of time (well, more to the point, I have no time at

all) to read other blogs; I can barely keep up with posting to Murderati and my own blog. But I do click through on people’s signature lines sometimes to see what they’re up to; it’s an extension of my

natural writerly voyeurism.

And a certain pattern has emerged with the not-yet-published writers I spy on.

It goes something like this: “My current WIP is stalled, so I’ve been working on a short story.” “I’ve gotten nothing done on my WIP this week.” “I have reached the halfway point and have no idea where to go from here.” “I had a great idea for a new book this week and I’ve been wondering if I should just give up on my WIP and start on this far superior idea.”

Do you start to see what I’m seeing? People are getting about midway through a book, and then lose interest, or have no idea where to go from where they currently are, or realize that a different idea is superior to what they’re working on and panic that they’re wasting their time with the project they’re working on, and hysteria ensues.

So I wanted to take today’s blog to say this, because it really can’t be said often enough.

Your first draft is always going to suck.

I’ve been a professional writer for almost all of my adult life and I’ve never written anything that I didn’t hit the wall on, at one point or another. There is always a day, week, month, when I will lose all

interest in the project I’m working on. I will realize it was insanity to think that I could ever write the fucking thing to begin with, or that anyone in their right mind would ever be interested in it, much

less pay me for it. I will be sure that I would rather clean houses (not my own house, you understand, but other people’s) than ever have to look at the story again.

And that stage can last for a good long time. Even to the end of the book, and beyond, for months, in which I will torture my significant other for week after week with my daily rants about how I will never be

able to make the thing make any sense at all and will simply have to give back the advance money.

And I am not the only one. Not by a long shot. It’s an occupational hazard that MOST of the people I know are writers, and I would say, based on anecdotal evidence, that this is by far the majority

experience – even though there are a few people like Rob, here, (or so he SAYS) who revise as they’re going along and when they type “The End” they actually mean it.

Even though you will inevitably end up writing on projects that SHOULD be abandoned, you cannot afford to abandon ANY project. You must finish what you start, no matter how you feel about it. If that project never goes anywhere, that’s tough, I feel your pain. But it happens to all of us. You do not know if you are going to be able to pull it off or not. The only way you will ever be able to pull it off is to get in the unwavering, completely non-negotiable habit of JUST DOING IT.

Your only hope is to keep going. Sit your ass down in the chair and keep cranking out your non-negotiable minimum number of daily pages, or words, in order, until you get to the end.

This is the way writing gets done.

Some of those pages will be decent, some of them will be unendurable. All of them will be fixable, even if fixing them means throwing them away. But you must get to the end, even if what you’re writing seems to make no sense of all.

You have to finish.

I’ve had a couple of weeks in which my page marker has not moved past the number 198 because I keep deleting. Nothing I write makes any sense. I don’t have enough characters, I’m not giving the characters I have enough time in these scenes, I have no conception of yacht terminology and am spending hours of my days researching only to find I’m more confused about how things work on a boat than when I started.

I have Hit. The. Wall.

Yeah, yeah, cue World’s Smallest Violin.

Because – so what?

It always happens. I’m not special.

At some point you will come to hate what you're writing. That's normal. That pretty much describes the process of writing. It never gets better. But you MUST get over this and FINISH. Get to the end, and everything gets better from there, I promise. You will learn how to write in layers, and not care so much that your first draft sucks. Everyone's first draft sucks. It's what you do from there that counts.

That is not to say you can't set aside a special notebook and take 15 minutes a day AFTER you've done your minimum pages on the main project, and brainstorm on that other one. I'm a big fan of multitasking.

But working on that project is your reward for keeping moving on your main project.

Finish what you start. It’s your only hope.

– Alex

==============================

Over on my own blog I have been doing breakdowns of different movies to illustrate the story structure techniques that I've been talking about here, and one of the films I'm analyzing is CHINATOWN, not just because it's a fantastic, classic movie, but because it's virtually one-stop shopping for all the story structure techniques I'm trying to illustrate.

And in the middle of this CHINATOWN story breakdown and analysis it struck me that the character of Jake Gittes is a virtual textbook all on his own on techniques of creating a great character. So while I'm trying to figure out how to handle doing a story breakdown that would fit on Murderati (they're very, very long, these things…) I did want to post on the character techniques that went into Jake Gittes that helped create a tragic and iconic detective for the ages.

Zoe had an excellent post on character pitches this week and I thought I'd piggy back on that today, because I've been thinking about this myself. As you all know my focus on these blogs I do on story structure is all about what tricks authors can take from filmmaking techniques to help with their own writing.

Well, there are tricks that authors can take from filmmaking to help with character.

Today’s example is the CHARACTER INTRODUCTION.

I’ve been breaking down HARRY POTTER AND THE SORCERER’S STONE for the online class I’m teaching and that movie is superb for this character technique. Every major character has a fantastic character introduction.

Character introductions are painstakingly developed by screenwriters because the making of a movie (at least in the past) almost always hinges on attachments – that is, attracting a star big enough to “open” the movie – that is, bring in enough box office on the opening weekend to earn back production costs.

When you have an actor like that, the studio will finance the movie.

(Okay, now we could go into the fact that lately studios are less and less willing to rely on stars to open movies and why, but this isn’t an article on film financing, it’s an article on character).

And since the character introduction is the first thing an actor will read ain the script, and may be the one thing that makes him or her decide to keep reading, that character introduction may be your one shot at the actor who will make your film or consign it to that grim warehouse (one of many grim warehouses) where scripts with no attachments end up.

Actors don’t always read the whole script. I am absolutely sure that all your favorite actors do. And there are actors who convince great directors to sign onto scripts that they love. There are actors who love a script so much that they produce it themselves, without even taking a role in it, to get it made.

Still, and I know you may find this hard to believe – some actors only flip through the script reading all their own lines, and make the determination of whether or not they will play a part from that.

And so no matter how brilliant the rest of your script is, an irresistible character introduction may be your one shot at getting an actor who can get your movie made.

But what does all this have to do with writing novels, you ask?

Well, what I’m saying is that even for novelists, it doesn’t hurt to think of character in terms of casting. I know some of you design characters (in novels as well as scripts) with actors in mind. I certainly do. You may start writing a scene imagining a certain actor playing the role of the character you have in mind, and use that actor’s voice. I do this, not all the time, but fairly often. I can feel myself writing for an actor, and imagining an actor saying the lines – but then ALWAYS, at a certain point, the character just takes over. Everything I do with character until that point is just treading water until the REAL character shows up.

Then I forget all about actors and creating and designing – I’m really just following the character around taking dictation.

But – until that point, imagining an actor, and writing for that actor, can be a real help in attracting that mysterious being called character.

(I would be worried about sounding completely psychotic at this point except that I’m talking to a bunch of writers and I KNOW YOU KNOW WHAT I’M TALKING ABOUT.)

So, if you’re willing to buy into this metaphor I’m working on, that characters are much like actors, and you have to design parts that will attract them to your story and convince them to take on the role…

A really good way to do this is to create an irresistible CHARACTER INTRODUCTION.

And even if you don't buy my mildly psychotic analogy, you've got to admit, a great character introduction might be what entices a reader who's browsing through your book to actually buy it.

Let’s take a look at some great intros from the movies.

– Rita Hayworth throwing back her hair in GILDA.

– Dustin Hoffman on stage playing a tomato in TOOTSIE (and then the equally classic introduction of “Dorothy”, struggling to walk down a crowded NY street in high heels and power suit.)

Hoffman as a tomato tells us everything about his character, both his desires and problems: we see the passion he has for acting, the fact that he’s not exactly living up to his potential, and how extremely intractable he has, basically unemployable. It’s also a sly little joke that he’s playing a “tomato” – a derogatory word for a woman.

– Jimmy Stewart as George Bailey in IT’S A WONDERFUL LIFE (see visual at top of post): “Nope, nope, nope, nope, nope, nope, nope. I want a BIG one.” And freeze frame on that handspan… fabulous, funny, sexy introduction. (That big, huh? Mmm.)

This intro also tells us something about George Bailey’s outer DESIRE line – he wants to do big things, build big things, everything big. In fact, the story will be about how all the LITTLE things George does in his life will add up to something more than simply big, but truly enormous.

– Mary Poppins floating down from the sky holding on to that umbrella.

– Katharine Hepburn in PHILADELPHIA STORY, throwing open the window shutters on a gorgeous day and exclaiming, “Good going, God!”

– And okay, let’s just look at HARRY POTTER, since I have it on the brain.

– Dumbledore: an elderly, medieval looking wizard regally walks down a modern street, using some flashlight-like device to kind of vacuum the lights from the streetlamps into this tool.

– MacGonegal: A cat on a porch meows at Dumbledore, then the shadow of the moving cat turns into the shadow of a witch in pointed hat, and MacGonegal walks regally into frame.

Hagrid: first appears as a glowing light in the sky, very conscious reference to Glinda’s magical appearance in the glowing bubble in THE WIZARD OF OZ (and Hagrid will be the fairy godmother to Harry). Then the Wizard of Oz reference has a humorous twist – Hagrid descends not in a shimmering bubble, but on a Harley.

But the introduction of Hagrid is more than humorous – it tells us a lot about the character. First, the debate that Dumbledore and MacGonegal have over whether Hagrid should have been trusted with the baby tells us a lot about this character we’re about to meet. And when we see Hagrid carrying the baby this hulking giant is as tender as a mother.

Harry Potter: we see him first as a baby in swaddling clothes, left on a doorstep (like every fairy tale changeling and also Moses in the bulrushes, the child who grows up to be the leader of his people), while the witch and the wizard talk about how important he’s going to be – then the scar on the baby’s forehead is match cut to the scar on 11-year old Harry’s forehead to pass time and introduce Harry again.

Again, note that this introduction of Harry tells us a lot about this character – in pure exposition and also by using the visual, archetypal references to Moses – and, let’s face it, the baby Jesus with the three kings (wizards and witch).

Olivander, the wand master: John Hurt slides into frame on a ladder, slyly glowing as only John Hurt can glow.

Nearly Headless Nick: pops his head right through the dinner table.

And a character introduction doesn’t have to be just a moment, either. As I said in another post, one of the best character introductions I’ve seen in a long time was the long build-up of Maria Lena, the Penelope Cruz character in VICKI CHRISTINA BARCELONA. With all of that anticipation and build-up, an actor is going to pull out all the stops when she finally blazes onto the screen, and Penelope totally did. That role was written to demand an Oscar-worthy performance, and she delivered.

Of course, having actors like all of the above has more than a little to do with the power of those introductions – obviously we’re talking about screen royalty here.

But those introductions were also specifically designed to be worthy of those stars.